What is OCD?

OCD stands for obsessive compulsive disorder.

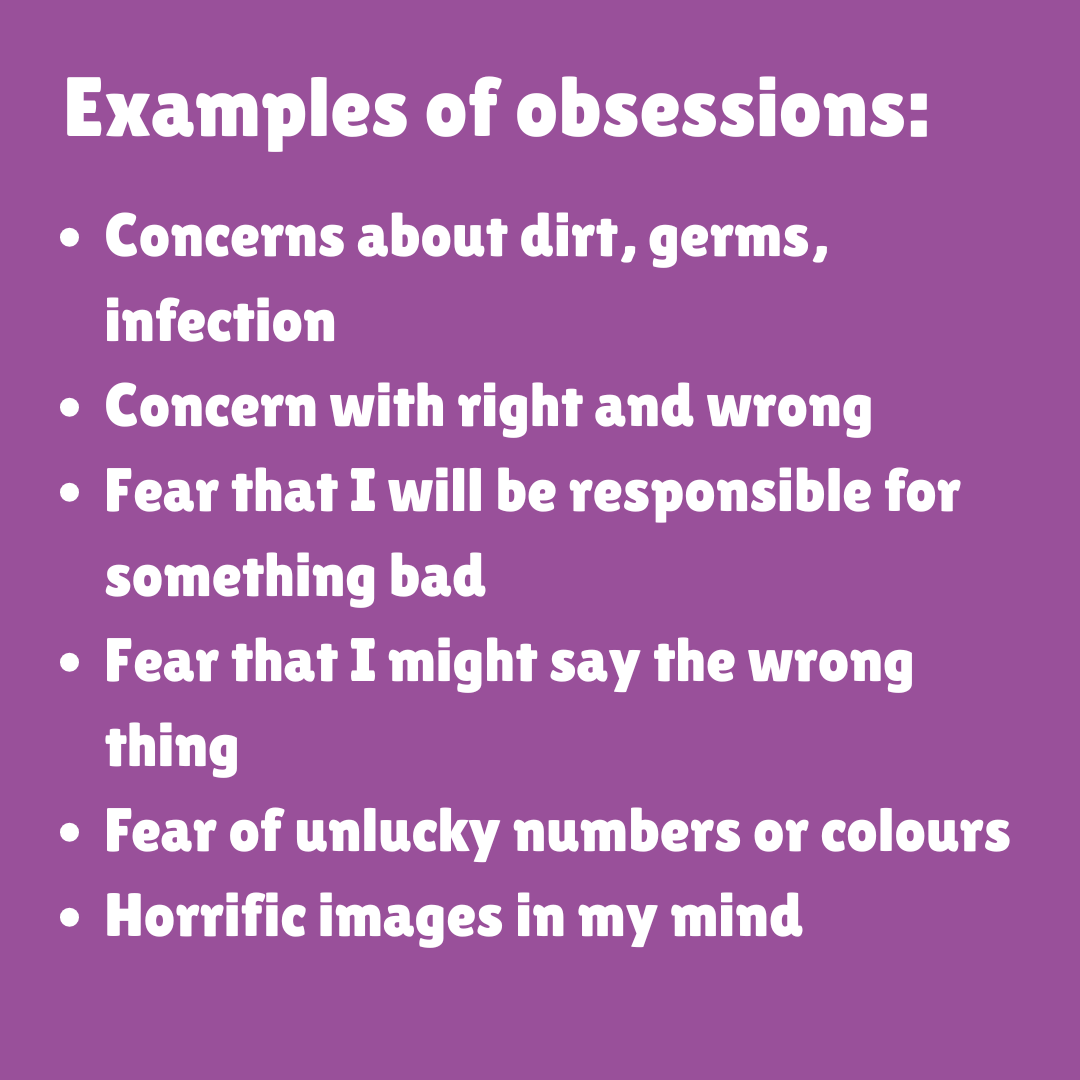

Obsessions are unwanted and intrusive thoughts, doubts, urges or images that will typically make the individual feel anxious or upset. Sometimes, obsessions in children and young people are only accompanied by a general feeling of discomfort.

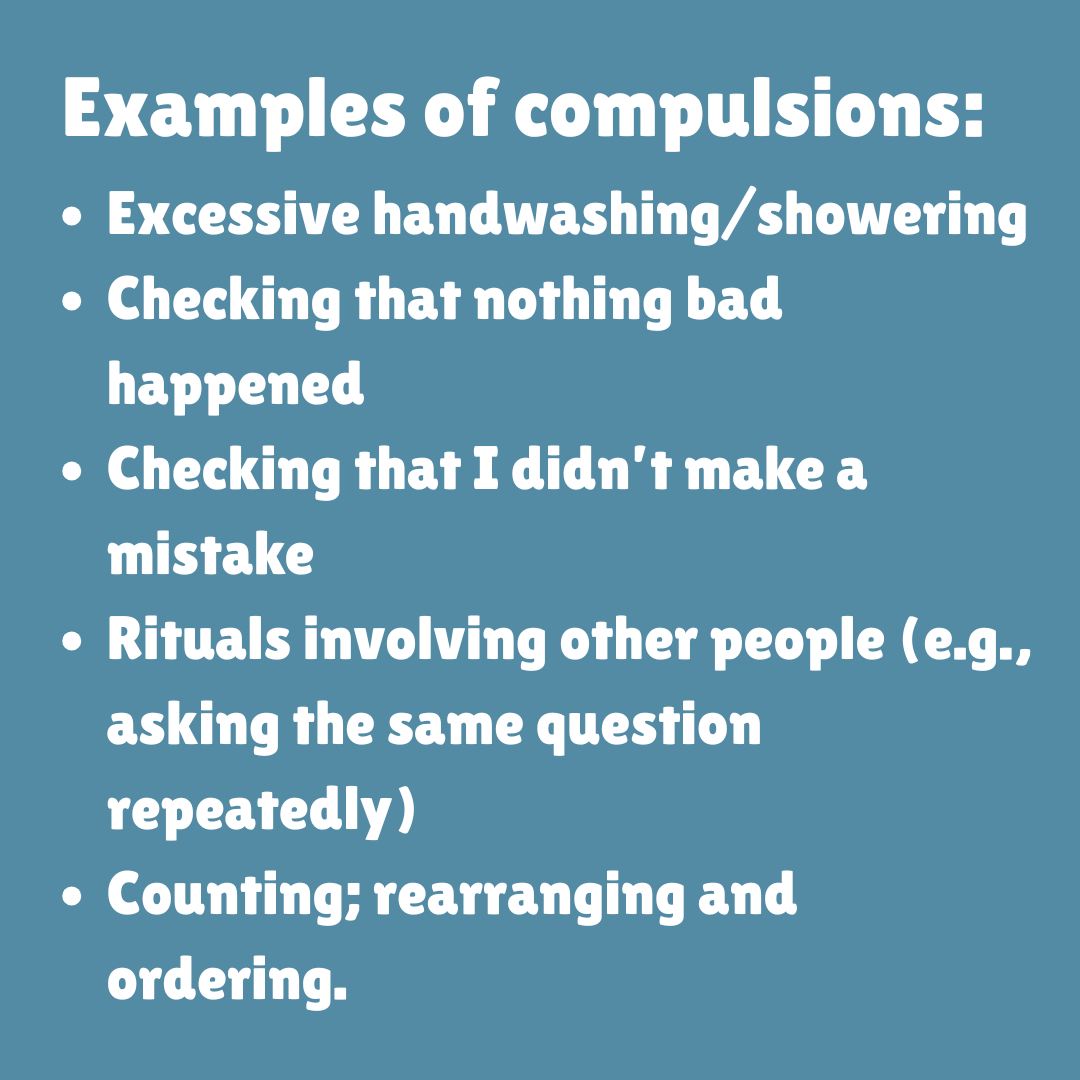

Compulsions are actions that a person does to try and make the thoughts go away. They are completed to reduce the anxiety or to make the uncomfortable feelings go away.

Many of the symptoms of OCD are things that everyone thinks about or does from time to time. Everyone has negative intrusive thoughts; however OCD makes people think about them more often than expected. OCD is normal anxiety gone wrong!

OCD is not a bad habit, and it is nobody’s fault. Like asthma or a broken leg, it is a condition that must be treated and managed. OCD occurs in approximately one in every 100 young people!

Many people have intrusive thoughts, or thoughts that make them uncomfortable, and this is normal. It’s very important to recognise that with OCD someone feels overwhelming anxiety and distress about a negative event happening if they cannot do the behaviour they want to. This helps us see the difference between negative and intrusive thoughts and OCD.

Externalising OCD

This involves helping you and your family to learn to see OCD as a problem that is separate from who you are. Obsessions and compulsions don’t represent your desired thoughts and behaviours. They are unwanted!

It can be helpful to externalise OCD by giving it a name (e.g. “bully”) or using “OCD” as an entity. For example, if a young person says, “my OCD made me count my socks several times”, this will help everyone to recognise that they didn’t want to count their socks, but their OCD wanted to. It was not their choice – it was their OCD’s choice. Therefore, a young person should not be blamed for their obsessions and compulsions. They should be supported and encouraged to fight their OCD symptoms – and externalising their OCD is a useful first step.

OCD is very good at tricking our thoughts and making us worry more than expected or making us worry about things that people don’t usually worry about. This is not very helpful and might makes us feel unhappy or uncomfortable. However, we do know that this is only our OCD talking – these are not my thoughts, these are my OCD thoughts.

One of the things you can do is to use helpful thoughts to 'boss' OCD back, and to let your OCD know that you are in control. This can be particularly useful when you start exposing yourself to your fears. Other people, such as family members or friends, can also use helpful thoughts to encourage you to 'boss' your OCD back.

Things you can do that may help

Examples of helpful thoughts

- I know this is just my OCD talking

- I don’t need to do what you tell me to do

- I am the boss, not you

- Go away, OCD/bully

- I won’t listen to you, and I will still be safe

Getting support to help you manage and overcome your OCD is important. Therapy can help you learn to recognise your OCD and teach you the skills to overcome it.

Help us improve our website

Please take a moment to share your thoughts and help us enhance our website by completing our short survey here.